|

What is the Matthew Bible, and a Brief History

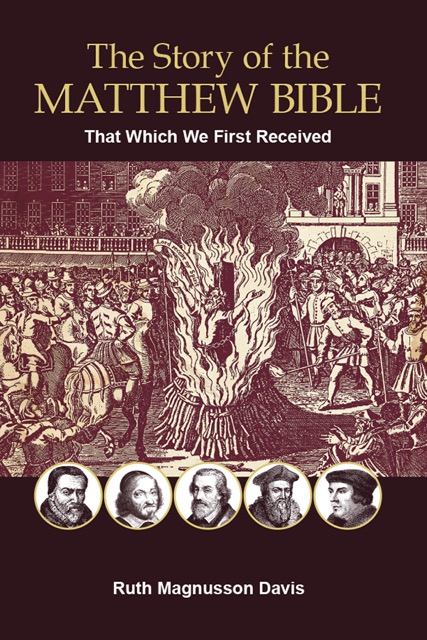

The Matthew Bible is a complete Bible, first published in 1537, which contained both the Old and New Testaments. It also contained the Apocryphal books, as did all Bibles, including the King James Version, until the 1599 Geneva Bible first excluded them. (The 1560 Geneva Bible included the Apocryphal books.) Sometimes, due to the name, people - and not only people, but also AI, as can be seen sometimes in Google enquiries - confuse the Matthew Bible with Matthew's Gospel. But, of course, Matthew's Gospel is just one book in the New Testament. As will be seen, the Matthew Bible also included many expository notes and study aids, and it was the world's first complete English study Bible. In the early 1500’s it was illegal to translate the scriptures. It was illegal even to own or to read an English Bible.1 To defy these laws could mean imprisonment, inquisition, torture, or death by burning alive at a public stake. Nonetheless, in face of such danger and persecution God moved and greatly used three men in the translation and production of the Matthew Bible: these three men were William Tyndale (c.1494-1536), John Rogers (c.1500-1555), and Myles Coverdale (c. 1487-1569).

William Tyndale: England was unsafe for a Bible translator, so William Tyndale worked in exile from hiding places on the continent. There, in difficulty and poverty, he began the great work of translating the New Testament from Greek into English. He believed God had called him to this work,2 and history has confirmed his calling. He was a learned man, a top notch grammarian, a lover of God’s word, and fluent in eight languages including German, Spanish, Greek, Latin, Hebrew which he learned later in life, and of course his beloved native English. In translating the New Testament, Tyndale worked largely alone, using the Greek scriptures compared and compiled from original manuscripts by the Dutch scholar Desiderius Erasmus. He also used a minimal number of other resources including dictionaries, grammars, and Martin Luther’s German translation. His New Testament was first published in 15263 and the little bibles, so small they could fit in your hand, were smuggled into England in bales of cotton, where people hungry for truth purchased them at great personal risk. William Tyndale: England was unsafe for a Bible translator, so William Tyndale worked in exile from hiding places on the continent. There, in difficulty and poverty, he began the great work of translating the New Testament from Greek into English. He believed God had called him to this work,2 and history has confirmed his calling. He was a learned man, a top notch grammarian, a lover of God’s word, and fluent in eight languages including German, Spanish, Greek, Latin, Hebrew which he learned later in life, and of course his beloved native English. In translating the New Testament, Tyndale worked largely alone, using the Greek scriptures compared and compiled from original manuscripts by the Dutch scholar Desiderius Erasmus. He also used a minimal number of other resources including dictionaries, grammars, and Martin Luther’s German translation. His New Testament was first published in 15263 and the little bibles, so small they could fit in your hand, were smuggled into England in bales of cotton, where people hungry for truth purchased them at great personal risk.

Tyndale later revised his New Testament, making many changes in the 2nd edition that was published in 1534. Some changes involved reverting to Hebrew manners of speech that were contained in the Greek, which he had not fully appreciated until he worked on the Old Testament. He also added prologues and explanatory notes in the margins, which he called “declarations” or "lights". He wrote in his preface to the 1534 edition:

If I perceive either by myself or by the information of others, that anything has escaped me, or might be more plainly translated, I will soon cause it to be corrected. However in many places, it seems better to me to put a declaration in the margin, than to run too far from the text. … (archaic English minimally modernized)

A further New Testament followed in 1535, with minor revisions, and this formed the basis for the Matthew Bible.4

As for the Old Testament, the ringing words of the book of Genesis and all the Pentateuch, which we know from the King James Version, are for the most part Tyndale’s. He first published the Pentateuch in 1530 (later revisions followed), and the book of Jonah in 1531. He had apparently progressed to translations of Joshua through Chronicles also, and possibly more,5 but these were not published before he was betrayed to his enemies and captured. After his betrayal, Tyndale was imprisoned for 18 months in Vilvoorde on the continent. In 1536 he was condemned for heresy and then ‘degraded’ (stripped of priesthood in the Roman Catholic Church), publicly strangled, and his body burnt at a stake. He was about 42 years old.

Thus it was that William Tyndale gave his life for English peoples, to give them the word of God.

John Rogers: After Tyndale's martyrdom, his friend John Rogers took possession of his manuscripts. Tyndale had met Rogers in Antwerp, and was instrumental in converting him from Roman Catholicism. Having Tyndale's work in hand, Rogers set out to publish a complete bible. To make up what Tyndale had not been able to complete, he used the the Old Testament and Apocryphal translations of Miles Coverdale. He added a lengthy Table of Principal Matters, a summary of basic doctrines of the bible, based upon that contained in the 1535 bible of the French reformer Pierre Olivetan. He added many other badly needed helps for readers who were then almost biblically illiterate. Altogether, it was a colossal job of compiling, editing, and organizing. Rogers then published the complete work under the name "Thomas Matthew" in 1537. It quickly became known as the Matthew Bible, or Matthew's version. In 1549, publishers Raynalde and Hyll issued a reprint, and a final edition appeared in 1551. John Rogers: After Tyndale's martyrdom, his friend John Rogers took possession of his manuscripts. Tyndale had met Rogers in Antwerp, and was instrumental in converting him from Roman Catholicism. Having Tyndale's work in hand, Rogers set out to publish a complete bible. To make up what Tyndale had not been able to complete, he used the the Old Testament and Apocryphal translations of Miles Coverdale. He added a lengthy Table of Principal Matters, a summary of basic doctrines of the bible, based upon that contained in the 1535 bible of the French reformer Pierre Olivetan. He added many other badly needed helps for readers who were then almost biblically illiterate. Altogether, it was a colossal job of compiling, editing, and organizing. Rogers then published the complete work under the name "Thomas Matthew" in 1537. It quickly became known as the Matthew Bible, or Matthew's version. In 1549, publishers Raynalde and Hyll issued a reprint, and a final edition appeared in 1551.

(Also in 1549, publisher John Daye issued a different version of the Matthew Bible, produced by a puritan named Edmund Becke. Among other things, Becke substituted many of his own commentaries. He added copious notes to the book of Revelation, based on John Bale’s 16th century book, The Image of Both Churches, which rails against the Roman Catholic Church. Becke’s edition contains the infamous “wife-beater’s” note, which is consistent with the often strident nature of his commentaries.6 It is Becke's version, not the true Matthew Bible, which has incorrectly been made available digitally on line, and also in facsimile format by Gre atsite.com, sold as "the Tyndale Bible" and the 1549 Matthew Bible.)

John Rogers was seized and imprisoned in the Marian persecutions and, in 1555, was burned at the stake for heresy. He was the first burning victim of Bloody Queen Mary, who was estimated by John Foxe to have burned alive over 280 men and women. Rogers left behind a wife and eleven children, one still sucking at the breast.

The Matthew Bible, therefore, is the true fruit of martyrs’ pens—the word of God purchased with blood. And we know from the scriptures and from history that blood is commonly the precious ink with which our God attests to a significant work and confirms its authenticity; it is his seal of approval. Furthermore, as to Tyndale's portion, the Matthew Bible scriptures can claim to be the first printed scriptures translated into English from the original Greek and Hebrew tongues.

Myles Coverdale alone survived the persecutions, fleeing to the Continent to work there on bible translation. Coverdale and Tyndale worked together on the Old Testament Pentateuch in 1529-1530, and later again in Antwerp in 1535-1536. Coverdale worked on many bible versions over the years, however his contribution to Matthew 's version was from his first translation of 1535. Bible historian A. S. Herbert (see below) comments that this was his best. I agree: to read the Psalms and Proverbs from his pen, as contained in the Matthew Bible, is to come into fresh and meaningful light. His prophetic books are very clear. Myles Coverdale alone survived the persecutions, fleeing to the Continent to work there on bible translation. Coverdale and Tyndale worked together on the Old Testament Pentateuch in 1529-1530, and later again in Antwerp in 1535-1536. Coverdale worked on many bible versions over the years, however his contribution to Matthew 's version was from his first translation of 1535. Bible historian A. S. Herbert (see below) comments that this was his best. I agree: to read the Psalms and Proverbs from his pen, as contained in the Matthew Bible, is to come into fresh and meaningful light. His prophetic books are very clear.

Coverdale's translation of the Old Testament and Apocrypha supplied the Matthew Bible with what Tyndale was unable to finish, except the prayer of Manneseh. Coverdale translated chiefly from Martin Luther's German translations, with reference also to the Latin Vulgate and other helps. Without doubt, the clarity and meaningfulness of Coverdale's Bible is thanks to Luther's influence.

Coverdale is noted for his renderings of the Psalms, which were carried into the Church of England's Book of Common Prayer. He also gave us many precious translations of the works of other men from the German language, including Otho Wermullerus. (These are available in Parker Society editions.) He died at an old age in his home country of England.

Who Was “Matthew”?

In its cover leaf, Matthew’s version of 1537 was stated to be translated by Thomas Matthew. Bible historian A. S. Herbert, in the Historical Catalogue of Printed Bibles, explains:

“Thomas Matthew” is commonly treated as a pseudonym of John Rogers, Tyndale's intimate friend, and the first martyr in the Marian persecution. But as Rogers only edited what is essentially Tyndale's translation, it seems more probable that “Matthew” stands for Tyndale's own name, which it was then dangerous to employ.7

William Tyndale's name remained “dangerous to employ” for some time to come. In 1543 the English Parliament "proscribed all translations bearing the name of Tyndale.”8 As the scriptures do tell us, no prophet is accepted in his own country (Luke 4:24). Therefore Matthew's Bible was so called at least in part to avoid overt acknowledgment of Tyndale's contribution. How or why Rogers chose the pseudonym “Thomas Matthew” remains a mystery, but the biblical inspiration is obvious. It is noteworthy that, when charged with heresy by persecutors during Queen Mary's reign, Rogers was identified as using the "alias Matthew". All things considered, including the number of contributors to the Matthew Bible and the politics of the time, it no doubt served several purposes. However Tyndale, who first published anonymously because he believed that God’s servants must not seek personal glory, would not have complained.9

The Importance of the Matthew Bible

The Matthew Bible is important for reasons this editor is still learning to appreciate.

1. Uncompromised Scriptures

For one, the Matthew Bible is a truly uncompromised English Bible. We say this because Tyndale, and Coverdale at the first, when working with the scriptures, were bound to no ruler or authority, no denomination, no political considerations, no requirement for consensus or compromise, but God only. Indeed compromise was not an option, either to assist in publication or distribution, or to earn the translators any favour with men, especially those in power, most of whom were opposed. No doubt this ensured the purity of the work; the Lord brought His word forth in English through chosen vessels at a time and in circumstances when He would stand alone in their concerns and affections, conscience and the Holy Spirit alone constraining them as they sought accurate expression. It is truly a separated work.

When we search the Old and New Testaments we see that it is most often the lowly and the separated whom God raises up to do His greatest works (consider Luke 9:48). Such were the fishermen and tax collectors who became God’s Apostles. And, in a different sense of course, such were the authors of the Matthew Bible.

2. The Real Primary Version of the English Bible

A. S. Herbert’s Historical Catalogue of Printed Bibles says of the Matthew Bible:

This version, which welds together the best work of Tyndale and Coverdale, is generally considered to be the real primary version of our English Bible.10

The fact that later translators were largely content to use the Matthew Bible scriptures as the base for their Bible versions demonstrates its great worth. Thanks be to God, the King James Bible was in considerable measure taken from the Matthew Bible. It has been estimated that the KJV New Testament is 83% Tyndale’s. Professor David Daniell reports:

The aim of [the KJV], stated in the 1611 preface, The Translators to the Reader, was “to make a good one better”. That this refers to the Geneva Bible—though for political reasons it could not be stated—is clear from the fact that whenever in that long preface the Bible is quoted (fourteen times) the authors do not do so from their own translation, nor from the Bishops’, but from the Geneva. Moreover, though nowhere do they acknowledge it, they took over a great deal of Geneva’s text verbatim, and in doing so they were taking over much of Tyndale, though they clearly went directly to him [Tyndale] as well.11

Professor Daniell adds:

William Tyndale's Bible translations have been the best-kept secrets in English Bible history…Astonishment is still voiced that the dignitaries who prepared the 1611 Authorized Version for King James spoke so often with one voice—apparently miraculously. Of course they did: the voice (never acknowledged by them) was Tyndale's.12

As to how much of the KJV was Tyndale's:

Though in the New Testament, and particularly in the Epistles, King James’s revisers made many changes, and though their base was Bishops’, the truth is that the ultimate base was Tyndale. A computer-based American study published in 1998 has shown just how much Tyndale is in the KJV New Testament. New Testament scholars Jon Nielson and Royal Skousen observed that previous estimates of Tyndale's contribution to the KJV “have run from a high of up to 90% (Westcott) to a low of 18% (Butterworth)”. By a statistically accurate and appropriate method of sampling, based on eighteen portions of the Bible, they concluded that for the New Testament Tyndale's contribution is about 83% of the text, and in the Old Testament 76%.13

Tyndale’s contribution to later Bible versions went largely unacknowledged, 14 but his ambition was not his own glory, but for God’s word, which was sufficiently preserved that it continued to bless Christians in the following centuries. Nevertheless, a good case can be made for bringing his work forth again, together with Coverdale's and Rogers' contributions to the Matthew Bible, so that people can compare Matthew's version with later ones and get a sense of what has been changed, added, or lost.

3. Changes and losses in subsequent versions

Although later revisions preserved much that was in the Matthew Bible, there were changes. A well known example is the substitution of the word “church” for Tyndale's “congregation” to translate the Greek word ecclesia. Tyndale discussed his reasons for this translation in his book An Answer to Sir Thomas More's Dialogue. This is discussed at length in "The Story of the Matthew Bible." However, this change has been eclipsed by many others over the years. The multitude of incremental changes to the original Scriptures will be thoughtfully reviewed in Part 2 of "The Story of the Matthew Bible: The Scriptures Then and Now."

4. Valuable notes, commentaries and introductions

There are many things worthy to be called treasures in the notes to the Matthew Bible, containing doctrines of the Reformation and of the ancient Church, and answers that are hard to find today.

5. Historical Value

The Matthew Bible has historical value. From it we learn about the struggles of faithful men who challenged apostasy and false teaching. Some of the notes touch on the issues of the day, and are not as bitter as some have made out. The Reformers lived in very dark times.

A Bible that Shows the Divine Hand

We believe the Matthew Bible to contain English scripture translations and commentaries greatly inspired by God, who worked through His chosen vessels raised up for that very purpose at that critical time, and that this martyrs' bible, sealed in blood, reveals the divine hand.

© R M Davis.

Endnotes:

1 The history of the Bible and William Tyndale are taken from: (1) Brian Moynahan, God’s Bestseller (New York, St. Martin’s Press, 2002) (2) David Daniell, Introduction to Tyndale’s New Testament (New Haven and London, Yale University Press, 1995), (3) David Daniell, William Tyndale, A Biography (New Haven and London, Yale University Press, 1994), and other biographies and Bible histories.

2 In his preface to The Parable of the Wicked Mammon, Tyndale wrote, “…in translating the New Testament I did my duty, and so do I now, and will do as much more as God hath ordained me to do.”

3 Facsimile copies of the delightful 1526 Tyndale New Testament are available now to the world at large, through any major book seller. Tyndale then put out a new edition in 1534 (actually followed by one more in 1535). Modern spelling editions of Tyndale’s 1534 New Testament and 1530 Old Testament, edited by David Daniell, can be purchased through any major bookseller.

4 A. S. Herbert, Historical Catalogue of Printed Editions of The English Bible 1525-1961, Revised and Expanded from the Edition of T. H. Darlow and H. F. Moule, 1903 (London, The British and Foreign Bible Society, 1968), 7.

5 Herbert, 18. See also David Daniell’s comments on the authorship of this portion of the Matthew Bible Old Testament, as contained in his introduction to Tyndale’s Old Testament,(New Haven and London, Yale University Press, 1992), xxiv-xxvi, or for another view, see Joseph Chester's biography of John Rogers (London, Lougman, Green, 1861), for example at page 58.

6 In a note to the end of 1 Peter 3, on the words “to dwell with a wife according to knowledge”, this sentence occurs: “And if she be not obedient and helpful unto him, endeavour to beat the fear of God into her head, that thereby she may be compelled to learn her duty and do it”. (Spelling modernized.)

8 Herbert, 19. In this ordinance it was also required that all the notes and commentaries in the Matthew Bible be obliterated, or they could not be put out for reading in the churches.

9 Tyndale later put his name to his work because others were taking it, changing it, and publishing it. He realized that readers needed to know who the author was, to consider if it was trustworthy.

11 David Daniell, Introduction to Tyndale’s New Testament, xiii. (See details in endnote 1 above)

12 Daniell, Introduction to Tyndale’s New Testament, vii.

13 Daniell, The Bible in English (New Haven and London, Yale University Press, 2003), 448. The reference to 76% is to that portion of the Old Testament that Tyndale was able to complete before his execution.

14 Daniell, in his Introduction to Tyndale’s New Testament at page xxviii, explains that this was largely because Tyndale was considered a Lutheran, and therefore a heretic. However the reasons perhaps went deeper than that, a question which is partly explored in other articles on this website.

Donate to the New Mattew Bible Project

|

William Tyndale: England was unsafe for a Bible translator, so William Tyndale worked in exile from hiding places on the continent. There, in difficulty and poverty, he began the great work of translating the New Testament from Greek into English. He believed God had called him to this work,

William Tyndale: England was unsafe for a Bible translator, so William Tyndale worked in exile from hiding places on the continent. There, in difficulty and poverty, he began the great work of translating the New Testament from Greek into English. He believed God had called him to this work, John Rogers: After Tyndale's martyrdom, his friend John Rogers took possession of his manuscripts. Tyndale had met Rogers in Antwerp, and was instrumental in converting him from Roman Catholicism. Having Tyndale's work in hand, Rogers set out to publish a complete bible. To make up what Tyndale had not been able to complete, he used the the Old Testament and Apocryphal translations of Miles Coverdale. He added a lengthy Table of Principal Matters, a summary of basic doctrines of the bible, based upon that contained in the 1535 bible of the French reformer Pierre Olivetan. He added many other badly needed helps for readers who were then almost biblically illiterate. Altogether, it was a colossal job of compiling, editing, and organizing. Rogers then published the complete work under the name "Thomas Matthew" in 1537. It quickly became known as the Matthew Bible, or Matthew's version. In 1549, publishers Raynalde and Hyll issued a reprint, and a final edition appeared in 1551.

John Rogers: After Tyndale's martyrdom, his friend John Rogers took possession of his manuscripts. Tyndale had met Rogers in Antwerp, and was instrumental in converting him from Roman Catholicism. Having Tyndale's work in hand, Rogers set out to publish a complete bible. To make up what Tyndale had not been able to complete, he used the the Old Testament and Apocryphal translations of Miles Coverdale. He added a lengthy Table of Principal Matters, a summary of basic doctrines of the bible, based upon that contained in the 1535 bible of the French reformer Pierre Olivetan. He added many other badly needed helps for readers who were then almost biblically illiterate. Altogether, it was a colossal job of compiling, editing, and organizing. Rogers then published the complete work under the name "Thomas Matthew" in 1537. It quickly became known as the Matthew Bible, or Matthew's version. In 1549, publishers Raynalde and Hyll issued a reprint, and a final edition appeared in 1551. Myles Coverdale alone survived the persecutions, fleeing to the Continent to work there on bible translation. Coverdale and Tyndale worked together on the Old Testament Pentateuch in 1529-1530, and later again in Antwerp in 1535-1536. Coverdale worked on many bible versions over the years, however his contribution to Matthew 's version was from his first translation of 1535. Bible historian A. S. Herbert (see below) comments that this was his best. I agree: to read the Psalms and Proverbs from his pen, as contained in the Matthew Bible, is to come into fresh and meaningful light. His prophetic books are very clear.

Myles Coverdale alone survived the persecutions, fleeing to the Continent to work there on bible translation. Coverdale and Tyndale worked together on the Old Testament Pentateuch in 1529-1530, and later again in Antwerp in 1535-1536. Coverdale worked on many bible versions over the years, however his contribution to Matthew 's version was from his first translation of 1535. Bible historian A. S. Herbert (see below) comments that this was his best. I agree: to read the Psalms and Proverbs from his pen, as contained in the Matthew Bible, is to come into fresh and meaningful light. His prophetic books are very clear.